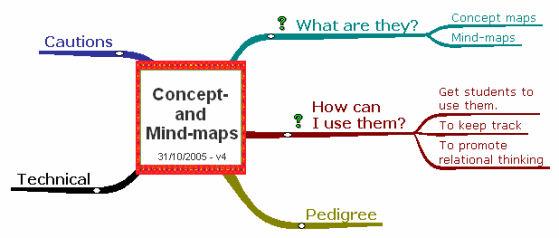

Click on the branches for the commentary

What are they?

They are simply kinds of diagrams or maps of conceptual rather than physical fields. [Back]

Concept maps

May have more than one central point and show how topics relate to each other in multiple ways.A concept map on concept mapping can be found here They are more flexible and less hierarchical than mind-maps, perhaps more suited to diagramming networks of connections. (But who cares about the labels? In many cases this is a distinction without a difference.) [Back]

Mind-maps

As appropriated by Tony Buzan (who seems to think he invented them; "mind mapping" is a apparently a registered trademark of the Buzan organisation), these are concept maps branching from a single central node; they are not as flexible as concept maps, but may be easier to manage by students in lectures, which notionally start from a single topic. [Back]

How can I use them?

How can you not? The main point is their capacity to reflect how we think. Few of us are totally linear and serial thinkers. If I look at any page of my note-books, I find I have naturally drawn connecting lines between ideas and topics; a concept map is simply an extension of this to lay out points visually. [Back]

Get students to use them

Many students will have been introduced to them at school, but may feel that they are not appropriate in the rarefied academic atmosphere of a university. Not so. They are a great way of organising lecture notes, particularly in the way in which they reflect the priorities of the subject.

Everyone's concept map of a topic will be different, and that's desirable. While there is quite a lot to be said for lecturers using them, it is the act of creating them which is more important than having a definitive "authorised" version. [Back]

To keep track

You can use developing and evolving concept-maps throughout a lecture (or a sequence of lectures) to show which topics have been covered (here in green) and which are current (here in yellow). They can of course start in a very basic form and be elaborated with new branches and connections as you go along. [Back]

Promoting relational thinking

Creating your own mind-map requires decisions about how topics relate to each other, and the nature of the connections between issues at the same hierarchical level, which encourage work at least at the multi-dimensional level of the SOLO taxonomy, and probably at the relational level as well.

Presentation packages tend to encourage us to reduce material to an unremitting barrage of bullet-points, gobbets of information related only by the order of their introduction (which is often not that important anyway), and it can be argued that this fragmentation of knowledge discourages making connections. Anything which re-connects material into a coherent body of knowledge is to be welcomed. [Back]

Pedigree

Pace Tony Buzan, look at a mediaeval "mappa mundi"; we tend to regard such maps as geographically naive, but they are as much about world-views as views of the world. They are firmly in the tradition of concept- and mind-mapping. Another source credits Leonardo da Vinci with inventing them. Concept maps, as diagrams, have been around for hundreds of years; Comenius' Orbis Pictus (1658) was probably the first to introduce labelled pictures into an educational text.

Concept maps really were invented by one person, Joe Novak. [Back]

Technical issues

There is a great deal to be said for drawing mind-maps in particular by hand; hand-drawn versions are far less constrained by the technical limitations of software, and are easy to annotate and expand (and rub out if done in pencil or on the whiteboard). If you are doing one yourself, why not build it up on a whiteboard or flip-chart as a live parallel to pre-prepared material on the projector?

- When taking reporting-back from small groups for an exercise where you know roughly what to expect, use a mind-map to lay out the reports; it organises the material very effectively.

- But keep them as simple as possible

Dyslexic learners often find mind-maps friendly, because the location of the text on the page provides an additional clue to its meaning. [Back]

Cautions

- Some people can make neither head nor tail of them.

- It is easy to overload them, both in content and connections; if using them in a presentation, and they are going to get complex, always start with a simple version and build it up. Apart from anything else, the text can get too small to read in a lecture.

- They are cryptic; don't rely on them exclusively

- Colour is an important feature of many maps; but show consideration to students who may have a degree of colour-blindness.

- (Its loopier manifestations are entertainingly exposed in Ben Goldacre's excellent "Bad Science" [London; Fourth Estate, 2008])Much of the literature about mind-mapping in particular is tied up with "brain-based learning", which is an idea which has many enthusiastic advocates but no rigorous and dispassionate research base, particularly in higher education. It's quite unnecessary theoretical baggage in any case. [Back]

Software

There is a lot of mind-mapping software available if you need to prepare maps on a machine, although simple concept maps in particular can readily be prepared in a simple drawing package, including those available in presentation applications within office suites.

- However, the excellent CMap Tools is a free download; the interface is a little idiosyncratic but it is powerful and easy to use once you get used to it.

The maps on this site were prepared with a very old version of MindManager. Other similar commercial packages are available, but note:

- FreeMind is a free, open-source package (which requires Java on your machine-but don't worry, it's easy to install). It is not as visually flexible as some other packages, but it's great for starters.

This is an archived copy of Atherton J S (2013) Learning and Teaching [On-line: UK] Original material by James Atherton: last up-dated overall 10 February 2013

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

"This site is independent and self-funded, although the contribution of the Higher Education Academy to its development via the award of a National Teaching Fellowship, in 2004 has been greatly appreciated."