Using OEC Games as Formative Activities to Connect International Trade Models with Real-World Data

Alejandro Riaño

City St George’s University of London

Published January 2026

Contents

- Abstract

- 1. Introduction

- 2. OEC Games as Formative Activities

- 3. Using Tradle to Motivate Theory-Oriented Discussion

- 4. Using Pick5 to Explore Production Technologies and Specialization

- 5. Implementing the Activities in Class

- 6. Conclusion

- References

- Appendix A. Instructor Guide

- Appendix B. Student Guide

Abstract

This teaching note shows how the Observatory of Economic Complexity’s games Tradle and Pick5 can be used as short, low-stakes formative activities to help students connect models of international trade with real export data. Tradle facilitates discussion of countries’ export baskets and overall patterns of specialization, while Pick5 encourages students to reason about the technologies underlying the production of specific products.

1. Introduction

Understanding the pattern of trade—what goods countries export—is a central learning outcome in undergraduate courses in international trade. However, students often find it difficult to relate stylized models such as the Ricardian, Heckscher–Ohlin (HO), and monopolistic-competition frameworks to the complexity of real export data. Regular, low-stakes engagement with actual trade patterns can help to bridge this gap.

This note proposes the use of two freely available online games developed by the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC)—Tradle and Pick5 (available at: https://oec.world/en/games)—as short formative activities that help students connect theoretical predictions about the pattern of trade with real export data. While Coon and Wooten (2025) show how Tradle can be used as an assignment to develop geographic literacy and broader awareness of the global economy, this paper focuses on informal, in-class use of the OEC games and highlights the distinctive contribution of Pick5, which encourages students to reason about the production technologies behind different goods—a key determinant of the pattern of trade. The games are easy for students to play and can be implemented at virtually any level of instruction, including high school.

2. OEC Games as Formative Activities

OEC games engage students with real trade data, helping them connect empirical patterns to theoretical models, promoting active, discovery-based learning and fostering diverse learning styles (Guest 2009; Asarta 2024); they can also develop students’ data-literacy skills (Hansen 2001; Halliday 2019). Because the activities require little preparation and take only a few minutes, they can be used repeatedly to highlight when standard models align with observed trade patterns—and when they do not (Holt 1999). For instance, students may notice export baskets that are unexpectedly diversified, such as Tunisia’s, compared with neighboring economies dominated by oil, or countries like Vietnam whose reliance on high-tech exports (such as telephones, computers and integrated circuits) resemble those of more advanced economies. These moments naturally prompt questions about underlying capabilities and production technologies: Which model(s) best explains these patterns, and what features—factor intensities, scale economies, or participation in global value chains—drive the global distribution of particular goods?

3. Using Tradle to Motivate Theory-Oriented Discussion

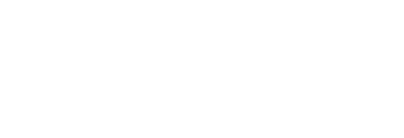

Tradle presents a country’s export basket and asks students to infer the country in no more than 6 attempts (see Coon and Wooten (2025) for a detailed description of the gameplay mechanics). Many daily puzzles feature countries with highly distinctive export structures—such as those dominated by oil, textiles, or agricultural commodities— which naturally invite Ricardian interpretations based on technological advantages or HO reasoning grounded in factor endowments. In contrast, highly diversified baskets typically indicate larger or more developed economies and can prompt discussion of increasing returns, intra-industry trade, and gravity forces.

The Tradle interface

4. Using Pick5 to Explore Production Technologies and Specialization

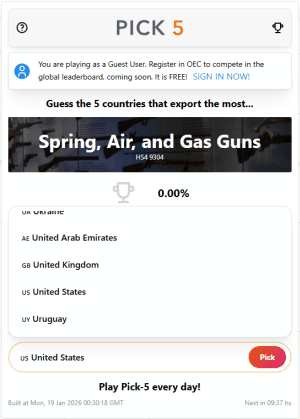

In Pick5, players attempt to identify the top five exporters of a specific product (at the Harmonized System (HS) 4-digit level of disaggregation), which—like Tradle— changes daily. After each guess, the game displays the country’s export value and global ranking for that product, providing immediate feedback that guides subsequent choices. Players earn bronze, silver, or gold cups depending on whether their selections account for more than 50%, 75%, or 90% of world exports.

Focusing on products rather than countries naturally leads to discussions about production technologies. Students can consider the factor intensities emphasized in the Heckscher–Ohlin model, the role of economies of scale in monopolistic competition, and the prominence of intermediate inputs in modern trade (Johnson and Noguera 2012; Antràs 2020)—key features of global value chains that are often not fully captured in the traditional models covered at the undergraduate level. Because many products are unfamiliar to students, instructors will often need to explain what they are and how they are used (e.g. cobalt oxides and hydroxides, HS 2822; oxometallic and peroxometallic acid salts, HS 2841; or carboxyamide compounds, HS 2924, to name a few). These moments of clarification create opportunities to discuss the nature of production processes and trade patterns revealed through the game.

A typical starting point is that students initially guess China, the United States, or Germany for almost any product. Pick5 quickly reveals when these default choices are appropriate and when they are not. Some goods—such as precision instruments, chemicals, or capital-intensive machinery—are indeed dominated by a small number of high-capability exporters, consistent with HO predictions or scale economies. Others are led by countries integrated into global value chains, where production is fragmented across stages involving assembly, processing, or component manufacturing. Because many featured products are intermediate inputs, Pick5 naturally leads to discussion of global value chains, task specialization, and the limitations of classic two-good, two-country models to modern trade data. Repeated use across the semester encourages students to think systematically about the characteristics of each product and the economic forces shaping its global distribution.

The Pick5 interface

5. Implementing the Activities in Class

Before introducing either game, it is highly recommended that instructors help students familiarize with the Harmonized System (HS) classification of goods, since both Tradle and Pick5 use export data reported at the HS 4-digit level of disaggregation. The HS is a hierarchical nomenclature developed by the World Customs Organization, where broader categories (fewer digits) encompass increasingly specific product groups (more digits). Understanding this structure is essential, not only because it underpins the data used in the OEC games, but also because it is a key element of international trade analysis often overlooked in undergraduate teaching. The HS classification forms the basis for collecting trade statistics, setting import tariffs, and defining rules of origin in free trade agreements.

Instructors can project the day’s Tradle or Pick5 and invite students to propose guesses individually, through an online poll, or in small groups. The goal is not accuracy but the reasoning students articulate and the discussion that follows. Because each game takes only a few minutes, these activities work well at the beginning or end of a lecture or recitation session. Appendix A describes in detail the implementation of the games in different settings. Appendix B provides a student handout that should help them to understand the connection between the games and the learning outcomes to be achieved with the activity.

The games can be played cooperatively—using the most common response as the class’s guess—or competitively, with groups taking turns to propose answers. Pick5 can be run similarly, with each group submitting a top-five list via an online form or on paper. Instructors may also add a competitive element by challenging students to “beat the instructor,” and, if needed, resolving ties with a light-hearted Tradle “penalty shootout.”

6. Conclusion

Tradle and Pick5 offer simple, flexible tools for helping students connect international trade models to real-world export data. Used as formative, discussion-based activities, they create frequent opportunities for students to interpret export structures, reason about production technologies, and consider the role of global value chains in shaping international specialization. While complementing earlier work on Tradle, this note emphasizes informal classroom use and highlights the particular value of Pick5 for deepening students’ understanding of how product characteristics influence global patterns of trade.

References

Antràs, P. (2020). Conceptual Aspects of Global Value Chains. The World Bank Economic Review, 34(3), 551–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhaa006

Asarta, C. J. (2024). Student engagement and interaction in the economics classroom: Essentials for the novice economic educator. The Journal of Economic Education, 55(1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2023.2269142

Coon, M., & Wooten, J. (2025). Leveraging Tradle to Expand Geographic Literacy in an International Trade Class. Journal of Economics Teaching, https://doi.org/10.58311/jeconteach/94271ca8d775a86681bc421dbdbd1758c7d5d948

Guest, J. (2009). Introducing games into an intermediate microeconomics module. Economics Network Ideas Bank https://doi.org/10.53593/n2a

Halliday, S. D. (2019). Data literacy in economic development. The Journal of Economic Education, 50(3), 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2019.1618762

Hansen, W. L. (2001). Expected proficiencies for undergraduate economics majors. The Journal of Economic Education, 32(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220480109596105

Holt, C. A. (1999). Teaching Economics with Classroom Experiments: A Symposium. Southern Economic Journal, 65(3), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2325-8012.1999.tb00180.x

Johnson, R. C. and G. Noguera. 2012. Accounting for intermediates: Production sharing and trade in value added. Journal of International Economics. 86(2): 224-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.10.003

Appendix A. Instructor Guide

Tradle and Pick5 can be played throughout a semester course in undergraduate international trade, especially in the first half, when models of the pattern of trade (Ricardian, Hecksher-Ohlin, Specific Factors, Monopolistic Competition) are often covered. Using the games repeatedly across several weeks strengthens students’ ability to relate theoretical predictions to empirical patterns and encourages students to use theoretical models as an analytical lens to interpret the complex patterns that arise in international trade flows in the real world.

Both games can be used in small and large classes with minimal preparation and take between 5-10 minutes to play (inclusive of discussion). Below I describe several ways of implementing them.

Large classes

Tradle (https://oec.world/en/games/tradle)

- Copy the day’s export basket in a PowerPoint slide together with the QR code that links to the Microsoft/Google form that students will use to provide their individual guess each round (recall that there are 6 chances to correctly guess the country in question).

- The form only requires one single text question: “What is your guess (country) for this round?”. After 2-3 minutes, view the responses and choose the most common guess and play it in Tradle online. Ask students to justify their choice:

- Are there any products that stand out (e.g. a large share of copper/copper ore exports would suggest the country could be Chile or Peru; cars and car parts could indicate Germany or countries in Central and Eastern Europe, etc.)? Another way to phrase this would be to ask students what they think are the sources of comparative advantage for the country in question— factor endowments (capital/labor/natural resources)? High levels of productivity resulting in specialization in high-tech products? Economies of scale?

- Is their choice being driven by the magnitude of total exports (To help students, the instructor can express the value of total exports as a share of world exports)?

- Is the concentration/diversification of the export basket informative about the country?

- After the instructor has inputted the guess for each round, proximity and cardinal distance to the correct country are revealed to students in real time. They simply need to refresh the form’s link to input their new guess incorporating the above information. Iterate on steps 2 and 3 until completion (or running out of turns). The instructor does not need to repeat the questions in part 2 in each round, but in the process of students’ zeroing on the correct answer, some of the questions can become more important—e.g. if students have found that the country is located in Europe, the value of total exports or the nature of second-order products might be the key clue to determine the right country (e.g. while cars and electric machinery are some of the most important exported products of Romania and Portugal, and both have similar total exports, the relative importance of textiles, leather or wine can help students distinguish between them).

- At the end of the game, students should consider the extent to which the trade models covered in class aided their identification of the country. For example, if the country in question is highly integrated in global value chains, like Mexico, Vietnam or the Dominican Republic, students might realize that the Heckscher-Ohlin model does not seem to provide—at least at first pass—a good account of these countries’ export baskets, which many students would expect to feature more agricultural products or low-skill-intensive goods like textiles, apparel and leather goods.

Pick5 (https://oec.world/en/games/pick-5)

- Present a slide with the product (HS 4-digit) of the day together with the QR code linked to the Microsoft/Google form that students will use to provide their guess about what are the largest 5 exporters of this product in the world. With Pick5, the form simply asks students “Guess the 5 countries that export the most <insert product here> HS XXXX” and provides 5 open text choices. Reveal the main use of the product in question to fix ideas, e.g. cobalt oxides and hydroxides are used as precursors for rechargeable lithium-ion battery electrodes and as pigments for glass and ceramic products.

- Ask students to justify their choices:

- What do they think are the factor intensities required to produce the good in question? Are there perhaps different technologies that can be applied depending on a country’s level of development (e.g. the production of cashmere sweaters might be quite different in Italy compared to Nepal or Bangladesh).

- How important are economies of scale in its production? That is, do students think that the product must be manufactured in large factories requiring intensive use of machinery and equipment involving large fixed costs?

- Is production likely to require access to advanced manufacturing techniques? Would it require the input of scientists, doctors or engineers?

- If the product is an intermediate input, would it make sense for its production to be located near countries with a strong comparative advantage in the downstream good? For example, Malaysia and Spain are two of the leading exporters of glycosides and their derivatives (HS 2938), an important input in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics—sectors in which countries such as Germany, Switzerland, and China are major global producers.

- Use the 5 most popular choices and input them in Pick5 online and reveal the percentage of world’s exports accounted for by the students’ guesses and whether they were able to achieve a bronze, silver or gold cup. Discuss whether students’ priors about the product’s technology and sources of comparative advantage stack up to the data. Pick5 is particularly useful to clear common misconceptions related to international trade—such as assuming China is always the top exporter of any given product or that small economies cannot dominate niche products.

Small classes

If you will have students working in groups during a tutorial/recitation, you can play the both games competitively (assuming that there are only a handful of groups); otherwise you can use the same set up for large classes described above. For Tradle, you can randomize (https://www.random.org/integers/) the group that gets to make a choice in given round.

In Pick5, you ask students to submit their top 5 choices in a piece of paper (or the same Microsoft/Google Form described before) and the winner is the group that guesses the most top-5 exporters. If the instructor has not already played the day’s game, they can challenge the groups to see whether they can beat the instructor in identifying the most top-five exporters.

If there is a tie between groups, it can be broken with a Tradle “penalty shootout.” That is, the teams with the highest number of correct guesses in Pick5, play Tradle sequentially to determine the ultimate winner of the day. It is worth noting that, even with a Tradle penalty tiebreaker, the entire activity still takes no more than 10 minutes to complete.

Appendix B. Student Guide

The OEC online games offer an engaging way to help connect abstract models of international trade to actual export data. When playing Tradle, consider the following questions to help you reason through which country the export basket belongs to:

- What are the dominant export products (those accounting for a large share of a country’s export basket)? How are these goods produced? Does their production require highly sophisticated inputs or high-skilled workers? Are the main export products natural resources?

- Is the export basket highly specialized or well-diversified?

- How small or large are the country’s exports in absolute terms?

With Pick5, consider:

- What are the main factors used in the production of the good (capital/labor/land)?

- How is the good produced? In small firms that could be set up easily anywhere, or in large factories that require involve high fixed costs of operation?

- What is the product used for? Is it intended for final consumption by households, or is it an input into the production of other goods? How easily can the product be transported?

After each game, take a moment to reflect on which of the models of international trade that you have learned in class best explains the observed pattern, what surprised you, and what you would guess differently next time. Keeping short notes across the semester can help track how your understanding of trade patterns evolves.