Evaluating the Flipped Classroom for Teaching Mathematics to Economics Undergraduates

Sara Navid

School of Economics, University of Bristol

Published May 2022

Abstract

This project evaluates the adoption of the flipped classroom approach for delivering small-group classes on a first-year compulsory mathematics unit to undergraduate economics students. A bespoke questionnaire collected feedback on students’ attitudes and beliefs towards flipped classes, the level of engagement with the subject material and the level of satisfaction with the design of their small group classes. Results reveal that there is a clear and strong preference for flipped classes over the traditional format as students hold a very positive perception of their learning in flipped classes. Moreover, evidence suggests that a majority of the students actively engage with the preparatory material prior to their classes and prefer to have the opportunity to work on additional unseen exercises in class with their peers. Recommendations, based on these results, are made to further improve the design of the unit’s small-group classes to enhance students’ learning experience.

Background, Motivation and Aim of Enquiry

Since 2018, I have been running small group classes for a compulsory first-year mathematics unit on the Economics degree programme. In 2019/20, the unit redesigned its small group classes, from the traditional to the flipped classroom format (defined in Box 1). As the class tutor, I observed greater peer-to-peer and peer-to-teacher engagement in flipped classes compared to traditional ones and a significant difference in the level of student engagement with the same subject material. These observations motivated me to consider if the flipped classroom format should be continued in this unit, possibly adopted more widely in the Economics programme and what we could do to further improve students’ learning experience in these small-group classes.

Collecting student feedback is an indispensable step when reviewing existing delivery and when considering wider adoption of any pedagogical tool, particularly during the early stages (Roach, 2014). Accordingly, this project aims to evaluate the use of flipped classroom by collecting student feedback on:

- their attitudes and beliefs towards flipped classes including perception of their own learning and level of engagement with peers and the subject matter in class, and

- the level of engagement with pre-class material and the extent of satisfaction with the design of their small-group classes

Box 1: traditional vs. flipped class format

The Traditional Class Format

Questions to be covered during classes are uploaded on Blackboard and students are required to prepare these questions prior to the class. During the class, the tutor reviews solutions to (some of) these questions and encourages students to participate and share their prepared answers.

The Flipped Class Format

Preparatory questions are uploaded on Blackboard and students are required to prepare these prior to the class. During the class, students work in groups to solve previously unseen questions. The tutor walks around to facilitate students’ progress, provide feedback and guidance and, when necessary, brings together the class to discuss particularly difficult material.

Design of the Mathematics Small-group Classes

Flipped classroom format as defined above, with two notable distinctions: 1) Solutions to the preparatory questions are not released until the end of the week i.e., after the week’s small group class has taken place and 2) The final class for this unit adopted the traditional format, as defined above, giving students the opportunity to cover solutions to the preparatory material in class, with no additional unseen questions.

Each class comprises approximately 15–17 students with the session lasting 50 minutes.

Why Flip?

The ‘flipped classroom’ is a type of blended learning approach which combines principles of student-centred learning with direct instruction. As the name suggests, the traditional learning process is ‘flipped’. Direct instruction moves from the group space (i.e. the classroom) to the individual learning space, as students are introduced to the learning material before the class, often with the aid of technology. Students familiarise themselves with the topic and participate in online activities, thereby achieving the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning, e.g. knowledge and some comprehension, before the class. The classroom (group space), is transformed into an interactive learning environment where the teacher guides and facilitates students as they actively engage with the subject matter, applying concepts learned through problem-solving activities and discussion with peers. The in-class time is therefore used to focus on the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning such as application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation, associated with more complex cognitive processes (Bloom et al., 1956; Lage et al., 2000; Houghton, 2004; Roach, 2014; Olitsky and Cosgrove 2016; Limniou, et al., 2018).

By engaging in this process, the role of the student changes from a passive listener and note-taker to an active participant and problem-solver, who partakes in the process of his/her own learning to develop autonomy.

The flipped classroom format also offers other benefits for student learning. The use of pre-class activities, for example, acts as the means for enhancing student preparedness while giving students the opportunity for self-paced learning in-class. Flipped classes also incorporate ‘just-in-time’ instruction as teachers can offer personalised help by addressing students’ misconceptions and confusions as these arise. By involving teachers and students in a continuous process of providing and receiving feedback, flipped classes also make ‘assessment for learning’ an integral element of the classroom (Roach, 2014; Olitsky and Cosgrove 2016; Limniou et al., 2018).

The efficacy of flipped classes, however, not only relies on the teacher’s ability to incorporate active learning strategies within the class but also upon the level of student preparation (Olitsky and Cosgrove, 2016). This makes it crucial for teachers to identify if students are adequately engaging with the preparatory material prior to the class. Gauging students’ perceptions of their learning in flipped classes is also crucial as a negative perception and experience will no doubt hamper student engagement (Roach, 2014). This project therefore aims to collect feedback on students' attitudes and perception of learning in a flipped classroom, their satisfaction with the design of their classes, and the level of engagement with the preparatory material for the selected unit.

Method: Data Collection

I designed a questionnaire which takes into account the idiosyncratic features of the small-group classes being evaluated. Beforehand, I consulted the literature, including studies focusing on evaluating the use of flipped classes in the Economics discipline as well others e.g. Psychology (e.g. Roach, 2014; Calimeris and Sauer, 2015; Becker and Proud, 2018; Limniou, 2018).

The final questionnaire was created using Microsoft Forms on Office 365. First-year students registered in the five groups I tutored for the Mathematics unit during the year were invited to take part in the survey via email. Each group comprised around 15–17 students. Students completed the questionnaire online in March 2020 and all (37) responses were anonymously recorded.[1]

Questionnaire

The questionnaire comprises two sections. Section 1 contains seven questions designed to gauge students’ attitudes and beliefs towards flipped classes, including perception of their own learning and level of engagement with peers and the subject matter in class. In this section, students respond by showing the extent of their agreement with the seven statements presented using a five-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral (i.e. neither agree nor disagree), disagree, or strongly disagree).

Section 2 contains 6 questions, designed to collect student feedback on two different aspects: 1) students’ level of engagement with pre-class material, with the addition of trying to understand reasons for non-engagement, e.g. level of difficulty or time restrictions, and 2) the extent of satisfaction with the design of small-group classes e.g. the timing of releasing solutions to the preparatory material, preference for additional unseen questions over reviewing preparatory material in class as well as the class length and size.[2]

Results and Discussion

Flipped v Traditional Classes

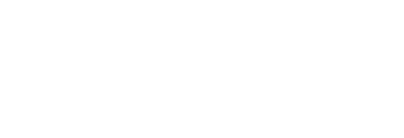

Section 1 of the questionnaire gauges students’ attitudes and beliefs towards flipped classes. Results from this section in figure 1 show an overwhelmingly strong preference for flipped classes over the traditional format, with 89.2% of students responding with strongly agree or agree to statement 1, which read: ‘I prefer the flipped class format’.

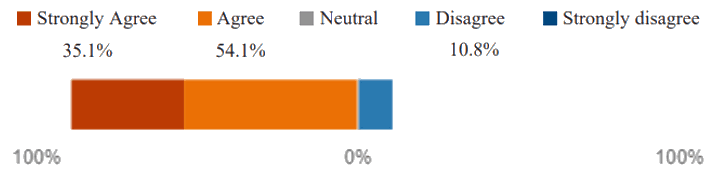

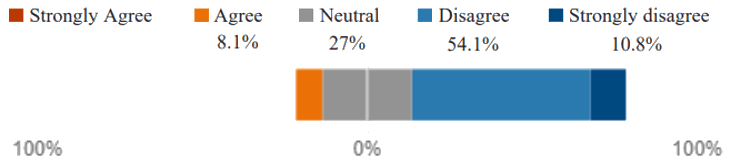

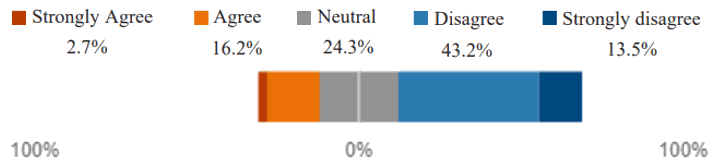

Statements 3, 5 and 6 encouraged students to reflect on their own learning experience during flipped classes. Again, results from these statements show that students hold a very positive perception of their own learning in flipped classes. For example, in response to statement 3, 51.3% of students agreed or strongly agreed that they learned new ways of solving problems by working with their peers compared to only 8.1% who disagreed while none strongly disagreed. Moreover, 73% of students reported that they work more in flipped classes than in traditional classes by agreeing or strongly agreeing with statement 6, compared to only 2.7% who disagreed and none strongly disagreed with this statement. Finally, 56.7% have reported that they believe they learn more in flipped classes by disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with statement 5, which read: ‘I believe I learn more in the traditional classroom’ compared with students who strongly agreed (2.7%) or agreed (16.2%).

Statements 2 and 4 further asked students to reflect on the level of engagement with their peers and subject matter in flipped classes. Here, in line with my observations as the class tutor, students have indicated greater engagement in flipped classes. In response to statement 2 for example, 75.7% of students reported that they enjoy working with their peers to solve unseen questions by agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement while only 5.4% disagreed and none strongly disagreed. Moreover, by disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with statement 4, 64.9% reported that they find flipped classes more engaging as these encouraged them to engage with the material more than traditional classes. Only 8.1% agreed with statement 4 and notably none strongly agreed.

Figure 1: Results from section 1 of the questionnaire

1. I prefer the flipped classroom format (where unseen questions are attempted in class) compared to the traditional class format

2. I enjoy working with colleagues to solve unseen questions

3. I learned new ways of solving problems by working with my classmates

Interestingly, by agreeing or strongly agreeing with statement 7, 59.4% of students showed preference for the class tutor to go through the solutions on the whiteboard as would be the case in most traditional classes. This finding does not necessarily contradict the above results as Roach (2014) notes that the onus of learning shifts to the students in flipped classes and thus they may suggest a preference for the alternative which takes this onus off them.

Overall, results from this section are similar to previous studies finding positive student perceptions of flipped classes in the Economics discipline (see e.g. Lage et al., 2000; Roach, 2014; Calimeris and Sauer, 2015). Thus, in line with previous research, results from this project show that students hold a very positive perception of their own learning and demonstrate high level of engagement with their peers and the subject matter in flipped classes. These attitudes and beliefs are very encouraging for the continued use of the flipped classroom format and the possibility of extending it to other units.

Figure 1: Results from section 1 of the questionnaire (cont.)

4. I do not find the flipped classroom format more engaging (flipped classes do not encourage me to engage with the material more than the traditional class format)

5. I believe I learn more in the traditional classroom format than in the flipped classes

6. I work more in the flipped class than in my other classes (which are run using the traditional format)

7. I prefer the class tutor to go through solutions to all the questions on the whiteboard

Engagement with Preparatory Material and Satisfaction with the Class Design

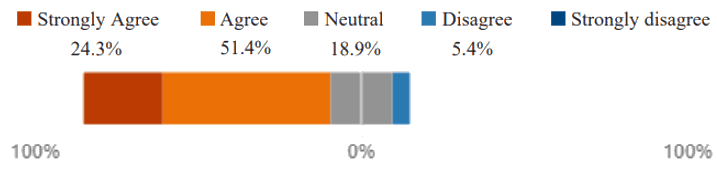

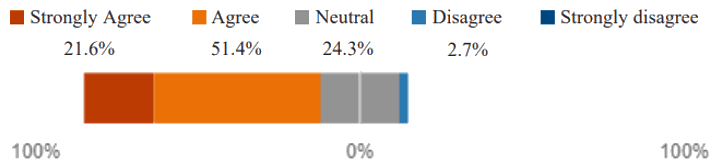

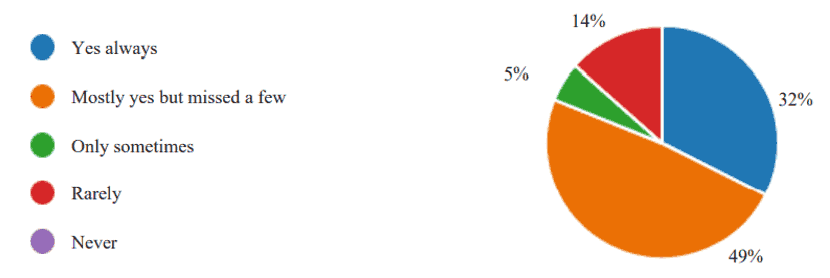

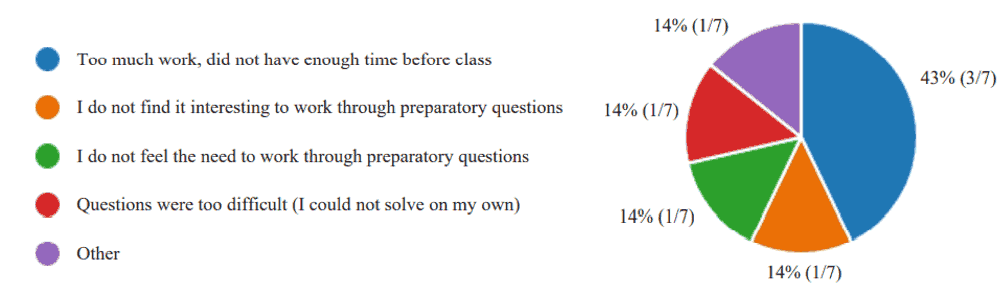

Section 2 of the questionnaire seeks feedback on students’ level of engagement with pre-class material and their satisfaction with their small-group classes. Results in figure 2 show that students engage well with the preparatory material, with 81% responding ‘Yes always’ (32%) or ‘Mostly yes’ (49%) to attempting the preparatory questions before the class in response to question 8, and only 14% responding ‘Rarely’. To identify the reason for non-engagement, students responding with ‘Only sometimes’ or ‘Rarely’ to question 8 are asked to specify a reason in question 9. Of the 7 students that selected these categories, 3 students (43%) selected ‘Too much work, did not have enough time before class’, with 1 student each (14%) opting for the other options ‘I do not find it interesting’, ‘I do not feel the need to work through preparatory questions’, ‘Questions were too difficult’ and ‘Other’ (no further details given). Although, the number of students is small, workload appears to be the main reason for non-engagement from the respondents.

Figure 2: Results from section 2 of the questionnaire

8. Did you normally attempt the preparatory questions before class?

9. If you have answered "Only sometimes", "Rarely" or "Never" to Q8, please specify the reason:

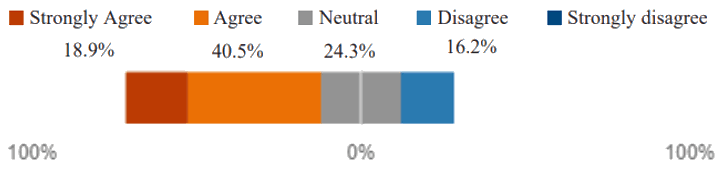

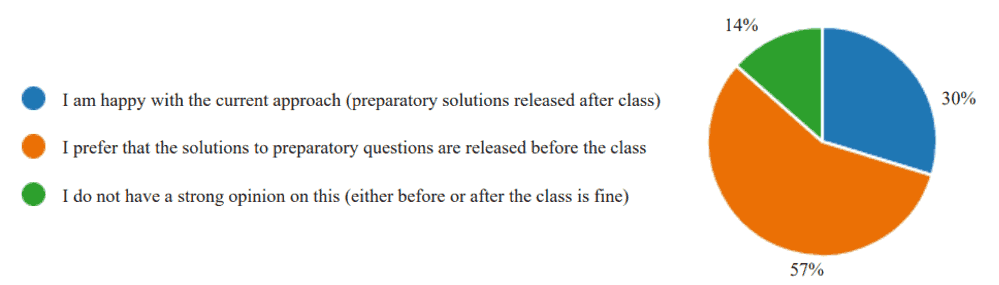

Questions 10 and 11 ask students to give feedback on two key aspects of this unit’s small-group class design. Question 10 examines students' views on the solutions to preparatory questions being released at the end of the week. In response to this question, 30% of the students indicated that they are happy with the current approach. A majority of the students, 57%, however indicated that they prefer solutions to the preparatory questions to be released before the class while 14% indicated no strong opinion.

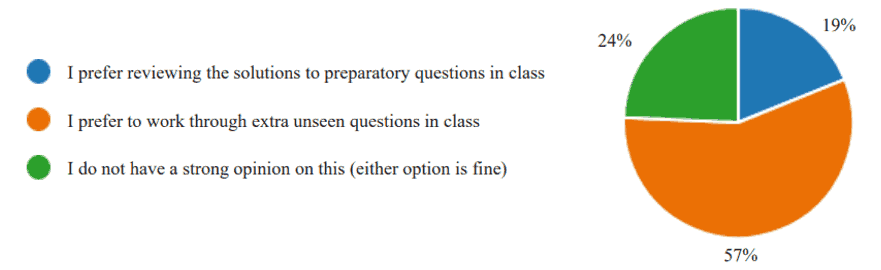

Question 11 examines students' views on the final classes where no additional unseen questions were attempted in class; instead solutions to the preparatory questions were reviewed. In response to this question, 57% of the students selected the option that they prefer to work on extra unseen questions, while only 19% showed a preference for reviewing preparatory material in class and 24% indicated no strong opinion on either option. Taking this feedback into account, it is recommended that solutions to the preparatory questions are released prior to the week’s class so students can review the material and identify weaknesses in their understanding, and additional unseen questions are made available to be covered in all classes.

Figure 2: Results from section 2 of the questionnaire (cont.)

10. In this unit, solutions to the (pre-class) preparatory questions were released at the end of the week. What is your opinion on this?

11. In this unit, the final classes covered solutions to the preparatory questions in class with no additional unseen questions. What is your opinion on this?

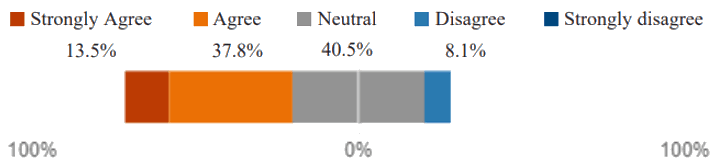

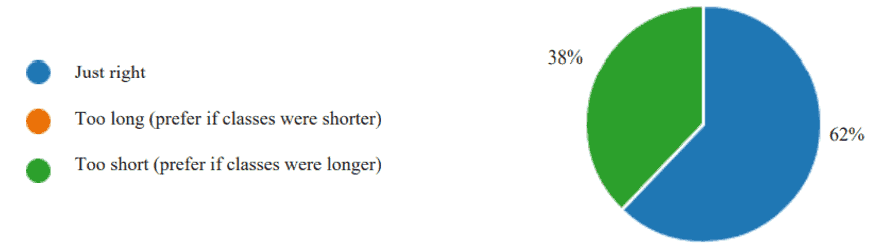

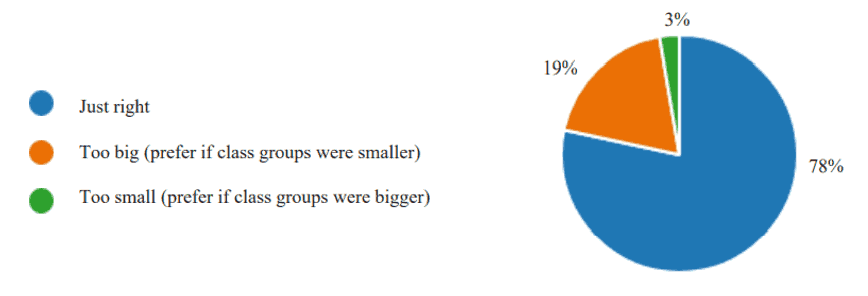

Finally, questions 12 and 13 ask students for their views on the length and size of their small group classes. 62% of the students indicated they found the length of their class to be ‘Just right’ while 38% suggested the class was too short (prefer classes were longer). None suggested that the class was too long. In response to question 13 on class sizes, 78% of the students indicated that they find their class size to be ‘Just right’, while 19% considered them too big with only 3% suggesting the class to be too small. Overall, student feedback suggests that a majority of the students find the class length and size to be just right although a minority would prefer longer classes and smaller groups.

Figure 2: Results from section 2 of the questionnaire (cont.)

12. Please indicate your opinion on the length of the classes

13. Please indicate your opinion on the size of the classes (i.e. number of students per class)

13. Please indicate your opinion on the size of the classes (i.e. number of students per class)

Conclusion

Student feedback gained in this project offers the opportunity to further improve the design of small-group classes in the evaluated unit. For example, a majority of students showed a preference for solutions to the preparatory questions to be released before the class and be given the opportunity to work on extra unseen questions rather than reviewing the solutions to preparatory questions during the final classes. Thus, to further improve student experience, it is recommended that solutions to the preparatory questions be released prior to the class and additional unseen questions are made available to be covered in all small-group classes.

As workload appears to be the most common reason expressed by the students who did not engage with the preparatory material, unit directors may want to consider offering short multiple-choice questions along with longer problem questions, to cater for the different abilities and time restrictions student face, in order to encourage student engagement and preparedness. Finally, as a majority of the students reported being content with their class size and length and a minority preferred longer classes and smaller groups, it is recommended that group sizes are maintained at 15–17 students per class and sessions lasting 50 minutes.

Overall, results from this project show that students hold a very positive perception of their own learning and demonstrate high level of engagement with their peers and the subject matter in flipped classes. These results are very encouraging for the continued use of the flipped classroom format in the evaluated unit and the possibility of extending it to other units in the Economics programme.

References

Becker, R., Proud, S. 2018. Flipping quantitative tutorials. International Review of Economics Education, 29, 59-73 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2018.01.004

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., Krathwohl, D. R., 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Brown, G., 2004, How Students Learn, published as a supplement to the Routledge Falmer Key Guides for Effective Teaching in Higher Education Series 1

Calimeris, L., Sauer, K. M., 2015. Flipping Out About the Flip: All Hype or Is There Hope? International Review of Economics Education 20, 13–28 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2015.08.001

Houghton, W., 2004. Learning and Teaching Theory. Engineering Subject Centre Guide: Learning and Teaching Theory for Engineering Academics. The Higher Education Academy, Engineering Subject Centre (Report commissioned by the Engineering Subject Centre, University of Exeter)

Lage, M. J., Platt, G. J., Treglia, M., 2000. Inverting the classroom: a gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. The Journal of Economic Education 31 (1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1183338

Limniou, M., Schermbrucker, I., Lyons, M., 2018. Traditional and flipped classroom approaches delivered by two different teachers: the student perspective. Education and Information Technologies 23, 797–817 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9636-8

Olitsky, N. H., Cosgrove, S. B., 2016. The better blend? Flipping the principles of microeconomics classroom. International Review of Economics Education 21, 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2015.10.004

Roach, T., 2014. Student perceptions toward flipped learning: new methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. International Review of Economics Education 17, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2014.08.003

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Yanos Zylberberg for his support in this project and Dr Steven Proud for his advice, support and invaluable feedback on an earlier version of the questionnaire.

Notes

[1] The response rate was lower than expected due to the mid-term disruption caused by the lockdown imposed in March 2020. Nevertheless, responses are insightful and allow clear conclusions to be drawn.

[2] The branching tool was used on Microsoft Forms for these two sections to ensure that follow-up questions build on students’ responses. For example, in response to Q8 “Do you normally attempt the preparatory questions before the class?”, if a student answered “Only sometimes, Rarely or Never”, he/she is prompted to answer question Q9 to specify the reason. However, if the student answered “Yes, or Mostly yes” to Q8, he/she is prompted to move on to Q10.