John Sloman, The Economics Network

and Caroline Elliott, The Economics Network and University of Warwick (formerly of Lancaster University)

First version published September 2002

Updated December 2023

Published as part of the chapter on lectures in the Handbook for Economics Lecturers

One way in which lectures can be made more interactive is to use an audience response system (ARS), sometimes called a ‘polling system’ or ‘personal response system (PRS)’, with ‘clickers’ and/or smart devices.[1] Universities are increasingly making such systems available in lecture theatres and other classrooms and they are becoming more and more popular with lecturers.

An ARS allows lecturers to ask students questions. Students then, either individually or in pairs, use a handset or a smart device, such as their phone, laptop or tablet, to answer the questions. If you are not familiar with it, the system is similar to the ‘ask the audience’ feature in the popular TV show, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? The handset, or ‘clicker’ as it is often called, is similar to a TV remote control. It has number and/or letter buttons. The students press these to answer a multiple-choice or numeric question. The handsets communicate with the lectern computer, or the lecturer’s laptop, which has a receiver inserted into a USB port.

Alternatively, students can access the relevant app on their smart device and use that to select the answers. The students log in to a particular URL at the beginning of the session. This has been assigned to the lecturer through the software. When they are on the site, they can then vote using their device. The results are displayed in the same way as with clickers. Some systems allow students to choose whether to use their own device or a clicker.

The questions can be given verbally, on an overhead projector, or in PowerPoint or Word using a data projector. The responses are then displayed on the screen at the front. Some versions of polling software have plugins for PowerPoint, which enable you to display questions in a separate PowerPoint file or integrated into your lecture slides. When students have voted, the lecturer will then click to allow the results to be displayed on the screen at the front.

With some polling software, you can record results by student. This enables you to set tests, although in most universities it is unlikely that you would be permitted to do this for summative testing (i.e. testing that contributes to students’ marks) without systems in place to prevent students communicating with each other.

The system

Some systems are free; others involve a charge and many universities pay a licence fee for a particular polling system.

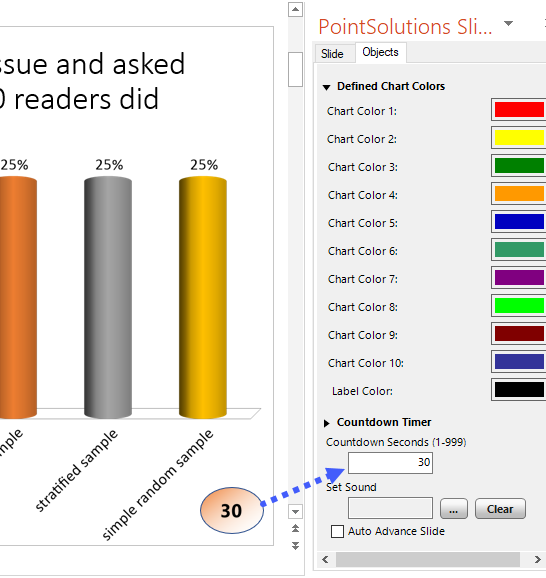

The market leader in UK universities is PointSolutions®, formerly known as TurningPoint®, which is part of the Echo360® suite of resources. You can design questions using PointSolutions, either within PowerPoint or separately. Universities using the system will normally have the software installed on classroom computers. The software can also be downloaded to your own laptop/desktop, either directly from Echo360 or from your university. You can then build questions in your own time.

In class, students can respond to questions either by using ResponseCard® or other handsets (clickers) or via the PointSolutions app, which can be downloaded to their own phones/tablets/laptops.

Clickers have the advantage that students are not distracted by their own phones, etc. They can only be used, however, in a physical classroom. Students’ own smart devices, by contrast, can be used anywhere and can thus be used for online/remote learning.

With smart devices, students simply connect to the login, enter the session number, which you have previously set up, and then a voting screen will appear each time you pose a question and then they simply click on their chosen answer. Universities can purchase licences for users. If, for example, they purchase 100 licences, up to 100 students can use the system at any one time. The licences can be used by anyone in the university – they are not restricted to specific students.

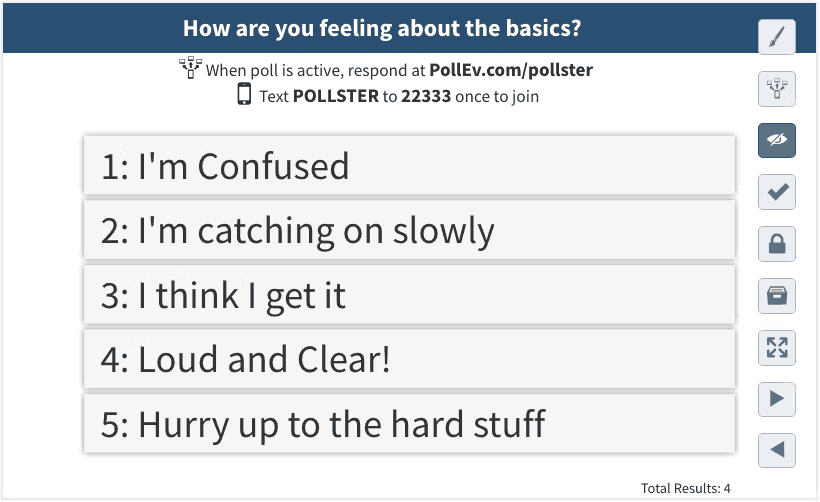

Another popular polling system that, like Point Solutions, has a PowerPoint plugin, is Poll Everywhere. This is not for use with clickers, only Internet-enabled devices. There is a free version that you can use with small groups (up to 40 responses per poll). Versions for more users and with extra features are charged by the number of responders. Lecturers have their own individual login and students access the lecturer’s URL at the beginning of the session. A disadvantage of this is that it does not enable PowerPoint slides with questions to be shared between lecturers. However, the interface is attractive and can be customised to suit your taste.

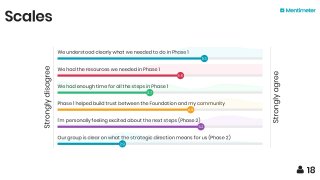

Other popular and often free polling systems where students use their smart devices over the Internet are Socrative, VoxVote, Slido, Vevox and Mentimeter. They are easy to set up and use and it is easy for students to respond using their phones or tablets/laptops, with the results displayed on the classroom screen via the lecturer’s computer or displayed online for online learning. For each session, the lecturer logs in and a unique session number is created for the students to access. Students do not need to sign up for an account and hence the systems cannot be used for testing. Students can also type short-answer responses, which are then displayed. Such questions, by their nature, will be better suited to small classes rather than lectures.

Other polling software is surveyed by Capterra.[2]

Use with PowerPoint

The software supplied with PointSolutions, Poll Everywhere and several other systems[3] is designed to make it easy to construct questions to be used in freestanding mode, or in PowerPoint or other formats. In the case of PowerPoint, most products add a toolbar to PowerPoint. This enables you to incorporate questions into an existing PowerPoint presentation, which can then be used in lectures with the audience response system.

In most systems, you can simply write your questions on a PowerPoint slide, which could be freestanding in its own file or simply as one of the slides in a presentation. The software then allows you to add polling functionality to the slide. When the question slide is displayed, the students vote using their handset or smart device and then, when you click on the slide, the votes for each answer are displayed.

Modes

You can use an ARS in anonymous mode, which is probably suitable for most lectures, where the objective of polling is to improve student learning and to provide feedback to the lecturer rather than to assess or track students.

Alternatively, with PointSolutions and some other systems, you can identify responses by login or handset. Thus with logins or handsets allocated to particular students, you can grade these students’ responses. This might be useful for purely formative assessment or merely to track students’ progress or attendance. In certain circumstances, depending on universities’ regulations and where cheating is not possible, the systems could be used for summative assessment too.

_____________________

The rest of this case study focuses on the learning and feedback benefits of an ARS. Those Economics lecturers who do use one report a significant improvement in student learning and motivation.

First, Professor Caroline Elliott from the University of Warwick and Deputy Director of the Economics Network, in an article in the International Review of Economics Education (Elliott, 2003)[4] discusses uses she made of an audience response system, known as PRS (no longer available, but similar in functionality to PointSolutions), in a second-year Microeconomics Principles course when she was at Lancaster University.

Use on a Microeconomics level 2 module at Lancaster University

Having taught second-year microeconomics for a number of years, I was aware that it was a course that students have historically often found challenging. Further, in a lecture environment students may be unwilling to volunteer information regarding their level of understanding of material covered. Consequently, I primarily used the PRS questions as a means of anonymously testing students’ understanding of material recently covered. If, after observing the results of a question, I was concerned that students had not fully understood the material on which the question was based, I could briefly review the material for them, and also tailor follow-up tutorial content accordingly. I also used multiple-choice questions as a way of introducing a subject, asking students to apply their economic reasoning skills prior to being formally introduced to a new Microeconomics topic. In addition, I used the PRS to gauge how much information students had remembered about a topic from the first year of their economics degree studies. …

I can confirm that the PRS has provided a very useful means of checking students’ understanding of material covered, both quickly in the lectures and also after the lecture. This has meant that I can more accurately determine what material should be revisited in tutorials, as well as in the lectures. Further, I appreciate that it has offered students an easy method of gauging their own understanding, and comparing their performance against that of their peers. While some of these benefits also transpire from the active learning methods reported by Harden et al. (1968)[5] and Dunn (1969)[6], the PRS has additional advantages. Bar-chart summaries of students’ answers are produced and visible to the lecturer and students alike, while responses can also be accurately recalled after the lecture has ended, including the responses of individual students when the PRS is used in the named mode.

I have also found that the PRS has had a very significant effect on students’ performance in lectures, stimulating their interest and concentration, as well as their enjoyment of lectures. It has proved to be an excellent method of encouraging active learning, while offering a means of varying the stimuli received by students in a lecture environment. Furthermore, they have found the PRS very easy to use. …

At the end of the lecture course, I asked the students (anonymously) to complete a questionnaire about the PRS as well as a standard lecturer feedback questionnaire. The PRS questionnaire contained five statements to which students could respond by selecting answers 1 to 5, 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 denoting strong agreement. Students were also given the opportunity to add any additional comments at the bottom of the questionnaire.

To the statement ‘The PRS is easy is use’, the median response was 5 and the mean response was 4.96. I fully expected this result and believe that it was helpful that I introduced the students to different features of the technology gradually. Hence, I only explained about the high- and low-confidence buttons on the handsets after the students had used the PRS in a couple of lectures. Similarly, I only used the named mode of operation after a number of lectures in which the PRS was used in the anonymous mode.

The statements ‘Using a PRS has increased my enjoyment of lectures’ and ‘Using a PRS has helped my concentration levels in lectures’ both gave rise to encouraging median responses of 4 and mean responses of 4.3. Clearly, not only was I aware that using the PRS improved students’ alertness, but also the vast majority of students recognised that their concentration levels improved when using the technology. Unfortunately, it cannot be deduced to what extent this reflects greater active learning or the changes in stimuli received during lectures. ‘Using a PRS has encouraged me to attend lectures’ produced a median answer of 4 and a mean response of 3.6, with some students pointing out that they would have attended lectures anyway.

Potential benefits of using an ARS in lectures

There are several potential benefits from using an ARS system, depending on the context in which it is used. The first and probably most obvious one is that a lecture can be easily transformed from a simple transmission process, where essentially the role of students is the passive one of receiving, assimilating and recording information, to a much more active learning experience. By encouraging students to think about and respond to carefully tailored questions, students’ understanding and retention of material, both factual and theoretical, can be greatly increased.

The second benefit is that it makes the lecture more interesting. Not only is the student more engaged with the material, but the lecture becomes more fun. Most people enjoy a quiz. The instant results and immediate sense of achievement from answering a question correctly are great motivators – as is the desire to get the next question correct if you get the wrong answer! Lecturers may be cautious about using ‘fun’ as a motivator, but if students learn and remember more, then it would seem to be well justified.

This leads to the third main benefit. More interesting lectures and lectures where more is learned are likely to improve student attendance.

In addition to these benefits, there are some others, depending on how the system is used.

- It is a very efficient way of asking questions. The results can be shown immediately in the form of a bar chart (or other types of chart).

- It eliminates the ‘crowd’ effect of getting students to respond to questions by a show of hands. With a show of hands, for example, answer A tends to be selected much less frequently, and a popular answer is likely to encourage the ‘don’t knows’ to raise their hands too. With an ARS, it is virtually impossible for students to see what other students are selecting, except perhaps their neighbour.

- Sharing one handset between two students and allowing them to discuss the answer to each question can improve understanding as they can learn from each other.

- An alternative is for students to respond individually, with the results then displayed, but the lecturer does not reveal the correct answer. Instead, students discuss their answer with their neighbour in the light of the displayed voting. After the discussion, students vote again and then the lecturer reveals the correct answer along with an explanation. The discussion between the students can be a valuable learning experience as students reflect on their answers and consider why other students might have voted the way they did.

- At the start of the course, it can be used to establish personal characteristics of students, such as age, gender, what degree they are on, whether or not they have A-level Economics or Maths, whether they are straight from school, whether the course is compulsory or optional for them, and so on. Not only does this provide useful information for you as lecturer, but it is also a way of building awareness by students of the community of which they are part.

- It provides instant feedback to the lecturer on students’ understanding. For example, a large majority with the correct answer would suggest that students have understood and hence you can progress to the next section of the lecture. If, however, the answers are evenly spread between the alternatives is would suggest a general misunderstanding and you might want to go through the material again, perhaps in a slightly different way. If a large number of students have selected a particular wrong answer it can suggest a particular misunderstanding and you might want to address this.

- The system can be used to give the lecturer instant feedback on the students’ perception of the quality of the lecture. You would need to be brave to do this, but by asking the students to identify the best and worst aspects of your lecturing, you can adjust to this immediately rather than waiting for the class satisfaction survey or relying on anecdotal comments. Other questions might be on whether the pace is too fast or too slow, or whether there are too many or too few examples. Also any point of concern raised by individual students outside the lecture can be put to the whole class to test whether this is of general concern.

- It can be used to check on prior learning from prepared work. This not only provides an incentive for students to prepare for lectures, but again provides useful feedback to the lecturer. Similarly it can be used to check on understanding of material from the previous lecture.

- It can be used to establish students’ opinions on open-ended topics or policy issues, such as whether income should be redistributed from rich to poor or whether the government should cut taxes and also government expenditure by a corresponding amount. This helps the lecturer to balance discussion of advantages and disadvantages by directly addressing the views of the students.

- Classroom experiments and games can be easily conducted. These can be an excellent way of illustrating theoretical or conceptual points. You can find many such games on the Economics Network site.

- Revision sessions: a large proportion of a lecture could be given over to questions as a way of giving students practice for a forthcoming exam.

- If the system is used in the named mode, it can also be used to keep a record of attendance. In addition, students’ answers can be stored and used for identifying students who need support. In certain controlled conditions, it could also be used for summative assessment.

Possible drawbacks of using an ARS

Some lecturers worry about the time taken to distribute handsets and collect them in at the end. Typically, however, if distribution is carefully planned, this should take no more than a couple of minutes and hand-in even less, especially if students deposit their handsets into a box on the way out of the theatre.

If you are using an Internet system where students use smartphones, etc., then there should be no set-up costs at all. Some universities distribute personal handsets free to students at the beginning of the course and only charge for replacements. This too eliminates hand-out/hand-in costs.

Another concern is whether so much material can be ‘covered’ in lectures, given that the questions inevitably take time that could have been used for talking by the lecturer. The obvious answer to this question is that it is better to sacrifice some words for the sake of better learning. What is more, the sacrifice is likely to be small, given that the total amount of time devoted to questioning need be only a few minutes out of the whole lecture.

The use of audience response systems is also discussed in the handbook chapter on Creative uses of in-class technology.

Alternatives to an ARS system

One alternative, also discussed in the handbook chapter on Creative uses of in-class technology, is to use mobile phone text messaging to answer questions posed by the lecturer, to give feedback or to ask questions of the lecturer. Various software packages allow the lecturer to capture text messages and display them on the screen (see the section on mobile phones in the above handbook chapter). As that section states:

“The use of mobile phones in the classroom has the advantage of opening up discussions in situations where most students would not otherwise participate. Students’ anonymity and the ability to have more time to think about the question encourages larger numbers of students to participate. Students tend to enjoy the interaction and the activity helps to maintain concentration and focus.”

Notes

[1] Part of this case study is based on Sloman, J. (2023), ‘Using an Audience Response System (Polling System)’, Teaching and Learning Case Studies 15 (Pearson Education)

[2] Audience Response Software (Capterra)

[3] Polling Software with PowerPoint Integration (GetApp)

[4] Elliott, C. (2003), ‘Using a personal response system in economics teaching’, International Review of Economics Education, vol. 1(1), pp. 80–6, DOI: 10.1016/S1477-3880(15)30213-9

[5] Harden, R. McG., Wayne, Sir E. and Donald, G. (1968), ‘An audio-visual technique for medical teaching’, Journal of Medical and Biological Illustration, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 29–32.

[6] Dunn, W. R, (1969), ‘Programmed learning news, feedback devices in university lectures’, New University, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 21–2.

↑ Top