Steve Cook and Duncan Watson

Swansea University

Published February 2013

Part of the Handbook chapter on Assessment Design and Methods

The chapter has referred to the numerous mechanisms employed by instructors to assign grades and to therefore categorise a cohort according to ability levels. It is important, however, to recognise that they are also a multi-dimensional tool with which to encourage students to identify their own learning problems and indeed for teachers to recognise the limitations of their own assessment processes. This section provides a case study of two inter-linked courses that demonstrate such a multi-dimensional character and also describes how an economics programme can be constructed to ensure it delivers that primary requirement, to think and write like an economist.

a. Introduction

The inexperienced instructor will often perceive the essay as a self-fulfilling means to encourage the development of writing skills. This attitude neglects to take account of the time constraints facing students, which inevitably limit their development in this key area. Often encountering numerous deadlines that encourage a form of ‘just in time’ time management, learning how to construct ideas and convey them coherently becomes secondary to simply putting words onto the page (ostensibly regurgitating lecture notes). These conditions are not conducive to the refining of writing skills, which typically require continual and meticulous revision. In recognition of this issue, Economics departments will frequently seek a resolution by offering a dissertation option. However, these courses (and the individual supervisors) differ in the extent to which they nurture (and indeed teach) the skill of writing and that of time management that facilitates the writing process. The specific nature of these courses will differ, but we can typically conclude that a supervisory system will be adopted and a word limit of approximately 10,000 words will be employed. However, seeking that elusive goal of ‘writing like an economist’ requires careful consideration of curriculum design and course development processes. Economics, arguably the premier social science, is perceived to be a valuable discipline because of how it demands the ability to calculate and to quantify. In the right hands this guarantees that superficial untested conclusions are avoided, and provides precise policy recommendations that maintain a powerful subject influence. However, the claim that such proficiencies hold over the discipline can also be to the detriment of the other less influential, but equally vital, practical skills that include the delivery of ideas comprehensively and articulately to a reader. This tendency towards mathematical exactitude is arguably the Achilles’ heel of economics, especially in a plural post-modern world that has systematically questioned the prioritising of such absolutes. It certainly becomes a limitation when it impacts upon the effective teaching of the subject, and encourages a bias that neglects the discursive and philosophical skills that stimulate the mind to think laterally and question what is fixed. In general this tendency towards calculation favours an assessment system too focused on testing quantitative methods skills. Consequentially, the dissertation is then dictated to by the desire to exercise the practical value of the theoretical econometric courses provided earlier in the degree process and grading inevitably concentrates on how successful the student has been in assimilating and understanding these mathematical elements. The writing skills, so prioritised by the general course aims, become the casualty of dissertation chapters that are focused on copying and pasting technical expressions to advertise the complexity of the methodologies that have been utilised.

Below, a case study is provided that demonstrates how these problems can be avoided. In summary, it involves the creation of two inter-linked courses, Topics in Contemporary Economics and Applied Econometrics. This particular instance of cross-course symbiosis reveals how positive the effects of co-operative assessment can be, and how it can be used to ensure that the whole curriculum successfully tests the higher-order learning objectives.

b. The modules

i. Module 1: Topics in Contemporary Economics

To facilitate the enhancement of writing skills, this course tests literature review methods whilst also providing an opportunity to assess the student’s ability to undertake a significant piece of work that tests the following key characteristics of research methods in economics:

- Interdisciplinary research: ‘Economics is a separate discipline because it has its separate, distinct body of theory and empirical knowledge. The subject-matter areas using economics are inherently multidisciplinary. For example, consumer economics draws from psychology, natural resource economics from biology, and economic policy from political science. The various subject-matter areas are dependent on a common disciplinary base. Thus, while economics is a separate discipline much of what we eventually do with it- its applications- become multidisciplinary subject matter work’ (Ethridge, 2004).

- Problem-solving research: ‘Problem-solving Research is designed to solve a specific problem for a specific decision maker. [It] often results in prescriptions or recommendation on decisions or actions’ (Ethridge, 2004).

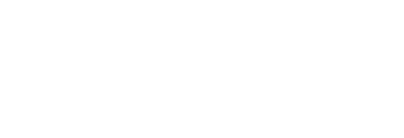

The dissertation module is given a weighting of 30 credits, thereby accounting for a quarter of the student’s final year of study. As shown in Figure 4, for Economics departments that offer dissertation options (84 per cent of our sample of departments do offer a dissertation), this is the most popular weighting applied.

Figure 4: A survey of Level 3 Economic dissertation credit weightings

(Credits; Percentage of institutions)

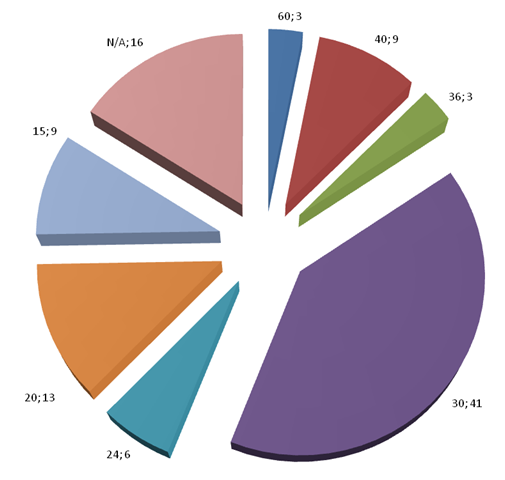

Aside from considering the weighting attached to final year dissertations, the nature of the associated assessment process can be considered. Rather than just simply submitting a final written dissertation and receiving marks for according to the quality of the writing, additional assessed elements can be included. From inspection of Figure 5, it can be seen that approximately one-half of our sample of departments (47 per cent) have dissertation modules and derive the student’s grade according to the final written submission. The standard dissertation will therefore involve the student working throughout the academic year, and find them heavily reliant on supervision guidance and randomised feedback for an understanding of their progress. This framework can cultivate two substantial deficiencies. Firstly, students can be subject to unintentional discrimination due to the differing level of support offered by individual supervisors. This is often due to unavoidable staff absences throughout the year and/or reflects differentials in workloads, although the varying definitions of what the role of supervisor should actually be can also play a significant part in creating disparity in how students are guided through the process. Secondly, given the other assessment demands imposed on students, there is also the risk of falling into the trap of procrastination where dissertation work is continually delayed for the sake of other deadlines. To minimise these problems a more structured format should be considered. Such structuring can also increase the likelihood that the skills associated with the course’s learning objectives are cultivated across the full range of student abilities. While smaller structured assessments can be linked to meeting ‘lower-order learning objectives of knowledge and comprehension’, as described in Dynan and Cate (2009), they can also be used to aid the ultimate delivery of knowledge transformation:

‘The cognitive learning strategy of comprehension-monitoring along with longer writing assignments, essay writings and research papers for example, should build on the short assignments and be linked to the higher-order learning objectives of complex application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation, or “knowledge transformation’’.’ (pp. 69-70).

Through a structured assessment regime the students receive regular standardised feedback and are able to link objectives in the short assessments to the ultimate aim of synthesis and evaluation.

Figure 5: A survey of Level 3 Economic Dissertation assessment weightings

(Written dissertation:Coursework components; Percentage of institutions)

Pertinent to the module’s approach to assessment are Tolstoy’s words:

‘every teacher must... by regarding every imperfection in the pupil's comprehension, not as a defect of the pupil, but as a defect of his own instruction, endeavour to develop in himself the ability of discovering new methods...’. (Schön, 1983, p. 66).

This introduces a key distinction in direction that is implemented by this module, whereby the up-skilling of both students and staff are inherently integrated within the assessment strategy. Hughes’s (2007) recommendation that academics should become ‘lead learners’ illustrates this philosophy, and it is one that is explored further by Rich (2010) who refers to a supervisory model in which the academic, by supervising a number of students doing dissertations in a related area, generates an ‘effective learning community’.

The creation of this ‘learning community’ could hypothetically create dissonance. There is a plethora of evidence suggesting that students enjoy dissertations for the sense of individual ownership that they create (e.g. see the review of undergraduate social science students by Todd et al., 2004). A team framework may compromise this sense of achievement. Thus it is a delicate balancing act that establishes a supportive communal environment that is not detrimental to individual intellectual endeavour and the most effective solution was created by Swansea’s Geography department. Here the supervisor role is replaced by a ‘dissertation support group (DSG)’ mechanism. Comprising of up to 10 students, the DSG experience is intended to provide support and facilitate a forum in which students can share and make considered decisions about their own dissertation research. Each DSG meets regularly to raise and consider issues that arise from individual dissertation projects. There are two types of meetings, which are detailed below:

- Peer-group meetings, where you meet without your mentor to discuss your research.

- Mentored group meetings, where your mentor is present to offer advice.

Peer-group meetings form the most immediate support mechanism, providing a forum for seeking and receiving advice on the challenges that dissertation research poses at any given time. Students are able to use these meetings for productive and genial exchange governed by the following principles:

- solicit comments on their research ideas and progress, seeking suggestions for improvement;

- ‘brainstorm’ ideas relating to both conceptual and practical aspects of their research;

- share ideas to help formulate an appropriate research design and methodology, involving constructive but critical review of their analysis;

- seek constructive solutions to any difficulties that they are encountering;

- collectively agree an agenda to take to the next mentored group meeting;

Mentored group meetings are thus student driven and structured to address the issues that have previously been ‘thrashed out’ and collated in peer-group meetings. Within mentored meetings students can expect the following:

- advice on issues previously identified at peer-group meetings;

- discussion of progress;

- guidance about the available literature on a specific topic;

- instruction in methodological techniques covered in other modules.

Assessment methods are then necessarily delimited by the creation of incentives to ensure that students fully embrace this system, take control of their own learning, and guarantee that meetings are constructive. This is achieved by a two-tier system:

Creating a log of DSG meetings

‘DSG Meeting Forms’ are completed individually at the time each of the DSG meetings occurs. The full sequence of forms should therefore provide a clear and detailed record of issues relating to individual research progress, as raised and discussed during DSG meetings. Forms should be regarded as a key tool for the student, enabling a process of reasoning and action that will assist the development of the dissertation. The ‘Issues to Raise’ section should be completed prior to each meeting, and records the matters arising from individual experience that the student wishes to discuss with the group. Similarly, the ‘Solutions Discussed’ section (to be completed during or soon after the meeting) need only contain detailed notes pertinent to individual concerns, although bullet points on the main concerns of the meeting are also required. When considering advice given by peers in response to individual concerns, any suggestions proffered must be recorded, as must any reflections upon the (in)adequacy of the solutions proposed, and the subsequent actions that would be required to fulfill them must also be documented. It is expected that the student be candid about group discussions and report occasions when they feel that the DSG has not facilitated any useful recommendations. They must, however, construct a reasoned critique of any advice that is considered flawed or inadequate.

Reflective summary

This is a two-page summary of how the DSG operated (including what worked, what did not, a description of individual contributions and how other group members assisted). Thus this mark is an individual score that is yet derived entirely from the context of mutual support. Frequently, students are found to discover common concerns and working out how to overcome these problems in a group is believed a valuable skill that takes them beyond university into the world of work. However, it also allows for a critique of the very methods employed by the course. This ensures that assessment feedback is multi-directional, with students becoming the primary agent of suggestion that improves course design.

A statistical comparison of the impact of the assessment changes on student performance, in contrast to the other case studies considered in this chapter, is made more complex by the time differences involved. With the traditional dissertation module suspended several years ago, subsequent changes in entry requirements could suggest that there are differences in mean capability. Further, whilst the traditional dissertation was typically taken by students on B.Sc. schemes, the new module is only compulsory for B.A. students. This could perceivably impact on the characteristics of the cohort. To investigate the impact of the changes on student achievement we therefore run a simple regression with controls for gender, degree scheme, A-Level entry points and the change in assessment methods. To ensure that we are comparing like with like, the marks for the Topics in Contemporary Economics module are restricted to obtainment in the final dissertation report (with all other assessment elements excluded). The estimates confirm the validity of controlling for degree scheme and A-Level entry requirements. However, they also confirm that the change in design has had a significantly positive effect on student performance. Other things being equal, they suggest that the student mark increases buy approximately 7.5 percentage points.

ii. Module 2: Applied Econometrics

The other module to be considered in this section, Applied Econometrics, was fortunate to receive funding from the Economics Network via its New Learning and Teaching Projects scheme in June 2010. The underlying motivation here was the desire to construct a module with by learning-by-doing and assessment-by-doing at its very heart. To that end, the module sought to examine students’ understanding and mastery of econometric tools and techniques via the submission of six projects, with the marks of the best five counting towards the mark awarded with a weighting of 20 per cent each. Given the range of material to be covered, the new module was introduced as a year-long, 30 credit unit to be compulsory for B.Sc. schemes (Economics, Business Economics, Financial Economics etc.) and optional for B.A. schemes. A range of objectives was identified, including (i) increased ownership and engagement on the part of the students via the use of continual project-based assessment, (ii) the development of subject-specific and transferable skills, (iii) the use of topics to enhance understanding on other modules taken by students and (iv) the more appropriate incorporation of developments in information technology. On the latter point, it is perhaps surprising that many departments seek to examine the ability of students to undertake and interpret econometric analysis via paper-based examination hall-based assessment, rather than practical exercises with data. Recent decades have witnessed astonishing advances in the computational power available to those interested in undertaking applied econometric analysis. As a consequence, the nature of econometric research has changed dramatically. To ensure students are provided with a true or relevant picture of what econometrics is and what it can achieve, these developments must be incorporated in its teaching. Alternatively expressed, consider the following quote from an interview with Professor David Hendry:

‘The IBM 360/65 was at UCL, so I took buses to and from LSE. Once, when rounding the Aldwych, the bus cornered faster than I anticipated, and my box of cards went flying. The program could only be re-created because I had numbered every one of the cards’ (2004, pp. 784–85).

The above quote presents a clearly dated picture of econometric practice in comparison to the current environment of large workshops containing high powered PCs providing access to a wealth of sophisticated, user-friendly software packages and a plethora of data sources and sites. However, if assessment of students is conducted via paper-based tests in examination halls involving discussion of the Durbin-Watson or Goldfeld-Quandt tests of the 1950s and 1960s, it is difficult to argue that assessment has kept pace with its underlying subject matter. This provided a major motivation for the present module and shaped both delivery and assessment for the module in an attempt to capture and fully utilise these developments. As a result, formal sessions involved the application and evaluation of a range of modern methods and techniques, with replication and evaluation of published research being one element of this to allow students to become more involved in the research they study. In line with its stated overriding objective, assessment followed a similar pattern. As a specific example of this, the delivery of, and assessment, relating to unit root analysis can be considered. As part of the delivery this year (2010–11), students were provided with a workshop exercise involving the replication of empirical results in a well known article in the Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. The subsequent assessment relating to this particular part of the ‘unit root section’ of the module adopted a similar approach, with an element of it requiring students to examine data employed in research published the Journal of Applied Econometrics to both replicate and extend work undertaken. In addition to providing students with practical experience to supplement lecture material, this form of exercise clearly illustrates the relevance of the methods considered and allows students not just to read but to become actively involved with published academic research that they study. In a similar fashion, later analysis of cointegration has been assessed not in a mechanical formulistic manner, but instead via analysis of the UK housing market to explore interdependencies and dynamic relationships between regions in the context of a particular posited economic theory. In each case, the intention was to demonstrate the relevance of economics (econometrics) within assessment via application to topical and important issues. As such the undeniably important formalities required for analysis are combined with a clearly defined goal or objective to (hopefully) overcome students becoming daunted or overwhelmed by the mathematical aspects of econometrics.

The ‘learning-by-doing’ emphasised here has been considered previously, at least to one extent, in the ‘teaching of statistics’ literature (see Smith, 1998; Wiberg, 2009). Similarly, in common with work such as Wiberg (2009), the current revised module was inspired by Kolb’s experiential approach to learning. As is apparent from a reading of Kolb (1984) and Kolb and Fry (1975), Kolb’s learning circle has four stages comprising of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. This provides an excellent basis for the structuring of the newly proposed module which presents students with specific examples of econometrics in action. With the present module, the concrete experience appears in computer workshops before reflection occurs in subsequent workshop and lecture sessions. The final steps of abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation are then covered primarily via the project-based assignments set for the students to undertake.

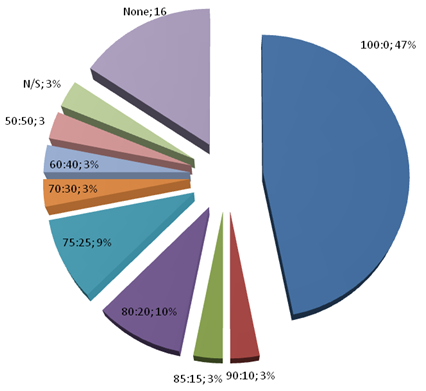

In light of the above discussion, two obvious issues concern the extent to which other institutions employ coursework in their assessment of econometrics for final year undergraduates and how the changes introduced at Swansea have fared. With regard to the former point, this is illustrated by the results presented in Figure 6 where the examination: coursework split for the departments surveyed are provided. The most popular form of assessment is clearly via end of module examination only, with very few departments considering a module with even as much as 50 per cent coursework. Of the departments examined, one institution (which corresponds to 3 per cent of the institutions included) did employ assessment via coursework only. However, this was on the basis of a single piece of coursework rather than multiple projects each designed to address particular elements of the module. With regard to the final 12 per cent of departments surveyed, 3 per cent did employ a mix of examination and coursework which was not specified (N/S) while 9 per cent did not provide final-year econometrics.

Considering the impact of these changes upon observed module outcomes at Swansea, Table 2 presents number of students enrolled on the Applied Econometrics module, the increase in the mean module mark following the introduction of revisions to the module and the average difference between the marks obtained by students on the Applied Econometrics module and their marks elsewhere. Again, the impact of any single underlying factor is difficult to quantify as a number of changes have occurred. In addition to assessment changing in nature and frequency, the number of students enrolled on the module changed as a result of the module becoming compulsory on some schemes, and the weighting trebled from 10 to 30 credits. However, the results are relatively straightforward to interpret, to some extent at least. First, a 10 per cent point increase in the mean module mark is apparent in the year following assessment changes. In addition, the difference between the average mark obtained by students on this module and their marks elsewhere has increased from 1.7 percentage points to 9.2 percentage points. By comparing the marks on this module with the average obtained by students elsewhere, a cohort effect is controlled for, to some extent at least.

To assess student opinion on the revised module, specific questionnaires were circulated in addition to standard in-house student questionnaires employed for all modules. This supplemented anecdotal evidence obtained and the discussions of student-staff committee meetings. However, a further extremely revealing source of information on student opinion utilised was an Economics Network Focus Group specific to the module which was conducted in February 2011. The results of these alternative methods produced some very pleasing feedback. Summarising these, it can be noted that students welcomed the introduction of the revised assessment framework as a means of:

- Increasing engagement and ownership: it was noted that hard work resulted in increased understanding and good marks.

- Embedding knowledge: it was stated that in contrast to preparing for formal examination, the new scheme allows knowledge to be gained and, importantly, retained. Comments included ‘you’re actually remembering it and learning, so if anyone asked me about my course I am going to explain it well… maybe to a potential employer’.

- Providing motivation for study and highlighting the relevance of material covered: a strong emphasis was placed upon providing a clear demonstration of the relevance and importance of econometrics within the assessment process. The feedback overwhelming supported this with comments such as: ‘You actually get something that I can apply rather than this is the knowledge and that’s the end of that’ and students having ‘a good sense of achievement’.

- Increasing the effectiveness and use of feedback: this has proved to be a very positive development. As feedback on projects is provided ahead of the submission of further projects, the form of assessments upon which feedback is provided matches that which is to be undertaken subsequently. This contrasts to standard modules where feedback on coursework is often taken onboard ahead of subject assessment in an examination environment. The comments refer positively to generic and individual feedback, its usefulness for later assessment, and comment upon its speed, detail and descriptive nature.

Figure 6: A survey of Level 3 Econometrics assessment weightings

(Examination: Coursework component; Percentage of institutions)

Table 2

Level-3 Applied Econometrics

Student Numbers, Mean Mark and Relative Module Performance

|

|

Number |

Increase in Mean Mark |

Average Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2010–2011 |

39 |

10.4% |

9.2 |

|

2010–2011: Introduction of Project-Based Assessment |

|||

|

2009–2010 |

11 |

N/A |

1.7 |